There was an oil drum in the back yard at Margaret Laurence’s house in Lakefield, the one in which she burned the only draft of her last novel. When Andreas and I spent a weekend with her in ’76, we noticed the oil drum. As for the novel, it was apparently about a small-town teacher’s battle with fundamentalist Christians.

Carrie Mac, author of Last Winter, spoke last week at the 2023 Sunshine Coast Festival of the Written Arts, and the image of that oil drum came to mind when Carrie mentioned the effects of trigger warnings on her writing and and on her readership. As she was signing my copy of her latest book, I mentioned Margaret Laurence, and Margaret's pre-digital experiences of trigger warnings and censorship.

FOR SHARON. WAIT! MARGARET LAURENCE?!?

Margaret had always considered herself to be a spiritual writer, so it had wounded her deeply when she was accused of writing pornography. Then, it got worse. A local pastor mounted a campaign to have The Diviners banned as a text for teen-aged readers – readers in Grades 10-12 no less. Readers who were surely mature enough to read The Diviners.

One of the stories that Margaret told us, about her experiences during this time, was that she had gone door to door in a nearby neighbourhood with a clipboard and done a survey. The first question was (as I recall): Should this book be banned? The overwhelming answer was yes. The second question: Have you read the book? The overwhelming answer was no.

At the School Board hearing where the decision to ban her books was to be made, Margaret read out the definition of pornography. A key element was that the passage or scene had to be sexually arousing. The pastor responded that yes, his understanding of pornography did fit that definition. Margaret then challenged him about one of the scenes that he had selected as being pornographic. It described a young girl in a changing room in a dress shop who had noticed two flies on the wall, one fly mounting the other. When this pastor affirmed that this scene was in his opinion definitely pornographic, Margaret had replied: I pity your poor wife.

We will never know how good or how bad Margaret’s final novel was. Maybe she’d been right to burn it. Maybe not. She often struggled with self-worth, once telling us after recently reading a Patrick White novel, that she’d needed to remind herself, again and again: This was his final draft.

In the aftermath of the censorship of Margaret’s books – which still continues to happen from time to time - some things have changed for the better. In Canada, we now celebrate Freedom to Read week. On the other hand, the internet has upped the lethality of anti-novel and anti-novelist bullying. Sadly, protecting writers and writing against all this and more continues to be a work in progress.

In Carrie Mac's talk at the 2023 Sunshine Coast Festival of the Written Arts, she mentioned the impact of trigger warnings and mentioned that a Goodreads review of her latest adult book had included a content warning. I checked it out:

Content warning: suicidal thoughts and attempts, mental illness, parental neglect, death of children, child abuse, sexualization of children.

Even her publisher had felt the need to add a warning for Last Winter:

Content Note: this is an important book and a powerful depiction of extreme Bipolar disorder. It deals with sensitive subject matter, and we encourage readers to take care of themselves and their mental health while reading.

BTW - My trigger warning would be:

This is an excellent novel. You might not be able to put it down for hours at a time, and as a result may suffer from extreme pleasure.

How much are writers being silenced these days - either by trigger warnings or by the threat of trigger warnings? One author mentioned that they were still considering whether to delete an incidental character in their draft manuscript, a character who was a pedophile - even though this character didn’t actually act on his pedophilic impulses. Surely, over-sanitizing our fiction (and non-fiction, poetry, etc) can be as dangerous to us as over-sanitizing our homes can be. Our immune systems simply don’t get tweaked often enough to defend us.

Margaret Laurence died on January 5, 1987, at age 60.

I heard the news of her death as I was heading into a Mission City council meeting. One of my fellow aldermen had heard about it on the radio. Earlier in the day, I had mailed Margaret a “book” that Sabrina - our daughter (and Margaret’s god-daughter) - had written for her, a series of drawings and quatrains pasted onto sheets of red construction paper. We had known that Margaret was seriously ill, but we’d thought we had more time. When we had spoken with her on the phone the night before, she had sounded robust. We did not know that she would soon take an overdose of pills. She chose to die before her terminal cancer got even worse.

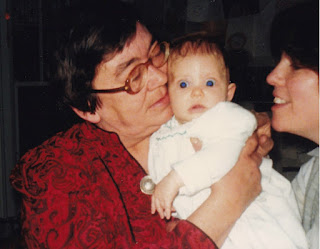

Margaret, her god-daughter Sabrina, and Sharon

Here is some irony. When I was reflecting on all this, I accessed a 39 year old CBC interview with Margaret on censorship only to find that it was preceded by an ad from Amazon touting their best prices for back-to-school stuff. The additional irony is that it is Amazon which now owns Goodreads and is also why it has become all too easy for amateur readers with personal agendas to silence a writer.

In a recent Globe and Mail article, Phoebe Maltz Bovy described an example of such silencing, the kind of silencing which led even Elizabeth Gilbert – a writer with a fair bit of clout – to feel compelled to pull her novel The Snow Forest from publication. Within days of it being announced, it had received 532 one-star reviews. Probably without even being read. The fact that it was set in Russia was too much for many readers. No matter that it had been written before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Bovy writes:

I have not read The Snow Forest. Nor, it would appear, have the Goodreads reviewers – over 170 of them, with commenting now turned off – so mad at its existence that they have given the book a one-star (lowest-possible) rating.

If incidents in which a book is panned out of existence before it even exists are not more common, it’s because, at every level of publishing, efforts are in place to prevent the creation of offensive content. Published authors emerge not from garrets, but from creative writing graduate programs, where they’re inculcated in the sensitivities of the day. Prepublication, they may seek out sensitivity readers, low-rung quasi-editors who vet the manuscript to see if it could plausibly offend members of an identity group to which the author does not belong.

Margaret deserves the final word: I do feel hurt. I do feel angry. But on the other hand, it can’t influence the way that I write, I have to write as much of the kind of truth as I see it. As I can. A writer has to remain true to her characters. Margaret Laurence speaks out against censorship. CBC Archives from 1984.