DISAPPEARANCES

1.

On June

19th, 2023, I stopped by the graveyard at St. Hilda’s Church in Sechelt, BC to

reflect for a moment on the lives of my parents. It is not far from

where I have lived for the past couple of decades, but I don’t drop by that

often. Maybe I should. On this day, I walked the

whole graveyard, looking for them, but they had totally

disappeared.

This was not

their first disappearance. Years ago, when the graveyard was being renovated, my mother's marker had also disapeared fromwhere we had expected to find it. It was eventualy found

leaning up against the back of the church. Somehow it had been set aside and forgotten during the

renovation. It had been removed because it had initially been installed outside the

legal boundary of the graveyard.

When it was reinstalled, it was no longer beside the church as it once had been, but instead was relocated down beside the main path. St. Hilda's had been chosen as the resting place of my parents, likely because my father had been the rector at the nearby St. Barts, in Gibsons, a church which had no graveyard.

At the time of my mother's burial, I was not living the Coast (as I do now), and

although I was at her funeral service at Pitt Meadows, I didn't travel to the Coast when her grave marker was installed. Was there an urn with

our mother's ashes buried there, or were her ashes just spread nearby? I can’t be sure. This was close to four decades ago.

When I visited

the graveyard on this recent June afternoon, a machine was busily cutting a wider

swath over the existing path, the path beside where my parents’ graves had last

been seen. I suspected that this renovation was likely the cause of their

recent disappearance. It turned out that the markers had been inadvertently

covered in dirt. This has since been removed. Once the path work is complete,

I've been assured, our parents' markers will get cleaned up to look as good as new.

The two small rectangles near the path are my parents' two grave markers.

Accidents

like this can easily happen. We are all human. I will be meeting with the church folk in

a month, after the work is complete, and am hoping that our family’s two

markers can have one more final move - that they can be placed closer together, as they once were. I will add a

photo when this final work is complete. This cemetery may be small, but it is well tended, and is a treat to spend some contemplative time in. It includes not only the parishioners of Sechelt, but also others like my parents from other parishes, and a Buddhist section which pays tribute to the local Japanese residents who were unjustly displaced after the bombing of Pearl Harbour. Blame for their losses of homes, land and livelihoods can only be laid at the feet of the cultural biases of the time.

2. Updated June 18, 2025 Added image of Mattie Skuce notes & error in her transcription.

Disappearances are also a fact of life (or death) in the Creggan Parish graveyard in

South Armagh, near Crossmaglen, but they have happened for other reasons and have had different consequences. Like St. Hilda’s, the Creggan graveyard is an inclusive graveyard. It has long included the

graves of a wide range of Church of Ireland, Presbyterian, and Catholic people.

For its time and place, this has represented a remarkable level of diversity

and inclusion. The only barrier, one that should always be kept in mind, was you had to able to pay for a plot, and then to employ a stone mason. When it comes to most graveyards - if not all graveyards - diversity only goes so far.

Fortunately, some of Creggan's lost graves have been

transcribed and recorded in journals.

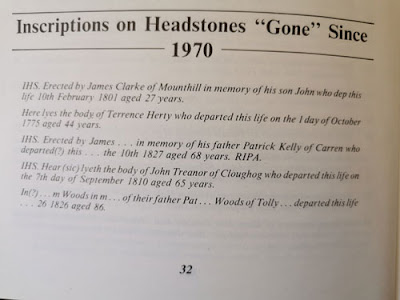

Known missing

graves from Creggan Guide to Creggan Church & Graveyard. Kevin

McMahon & Jem Murphy. p32.

The photos

which I took in 2010 show a lot of empty space in our family's JACKSON enclosure. This led me to wonder why there were only two visible grave markers: a large

rectangular piece of slate in one corner, and a few steps away a child’s

marker. Was something missing?

Christine WRIGHT (1941-2022) in background.

The JACKSON section is within the railed enclosure.

The JOHNSTON's part of the enclosure is behind it, inside a rock wall.

The 1785 parish records record the dimensions of this enclosure.

|

JOHNSTON-JACKSON. 26' x 16' of ground granted to

John Johnston Esq. of Woodvale in southwest corner with liberty to enclose

same and 16 feet square to Mr. David Jackson and family adjoining Mr.

Johnson's.

SOURCE: Armagh

County Museum, TGF Paterson manuscript No. 112 vol.1, Parish of

Creggan, Notes from the Church Registers Vestry books etc.

|

The child’s

grave-marker seen to the left was installed in memory of Edith Bradford JACKSON.

|

Sacred to the memory of Edith Bradford infant

daughter of Thomas and Amelia Lydia Jackson born 27th May 1874

died 7th September 1874: For such is the Kingdom of Heaven”.

|

A lot of

family history can be gleaned from grave markers, specially when dovetailed

with other records. From Edith’s death certificate, we learn that she had died

after a week of hydrocephalus, at Cavananore This was

the home of Edith’s great-aunt Mary Jane OLIVER (1821-1875). Edith's uncle,

Andrew JACKSON (1846-1929) who was at Cavananore at the time, was the official witness. He had likely been managing the farm for his spinster aunt. At

three months of age, Edith had been visiting at Cavananore with her parents

and siblings. At the time, they all lived in Hong Kong, where her father,

Thomas Jackson, (1815-1903), brother of Andrew, was manager of the Hongkong

and Shanghai Banking Corporation. It later became known as HSBC. He later became known as Sir Thomas, only the 2nd man from Creggan ever to be knighted (the 1st was Sir Henry O'NEILL in the 1600s).

Decades

later, it was Edith’s twin sister Amy Oliver JACKSON (1874-1962) who documented

with great accuracy much of the history of the JACKSONs of Urker (aka Urcher). She did

this work in collaboration with several of her cousins. They all benefited from the memories passed on from their grandmother Elizabeth JACKSON née OLIVER

(1815-1903).

As a result

of the efforts of these cousins, a transcription of this 2nd grave

marker can be found on a scrap of paper which I had photographed while staying with Christine WRIGHT (1941-2022) at Gilford Castle. Based on the style of

handwriting found on other such scraps of paper, this transcription was most

likely done by “Mattie” Maud Martha Elizabeth SKUSE née REED (1878-1958). She

was a daughter of Robert Hamilton REED & Margaret JACKSON (1853-1944), and also

a close friend of her cousin Mary WRIGHT née MENARY (1872-1946) of Gilford

Castle, daughter of Mary JACKSON (1844-1921). This 2nd transcription must have been saved at Gilford sometime before Mary WRIGHT’s death in

1946.

Mattie Skuse's notes of now missing grave marker.

Both the

transcription of Edith’s grave-marker as well as the transcription of this 2nd

JACKSON grave-marker were recorded in 1988 in the Creggan Guide to Creggan

Church & Graveyard, Journal of Creggan Historical Society, p31. Its

transcription matches Mattie's word for word. The dates

of death were for Thomas JACKSON’s father (David), his great-grandfather (John) and

grandmother (Elizabeth), as well as for Thomas'

great-great-grandmother (Margaret).

|

Here lieth the remains of John Jackson late of

Urker who departed this life the 20th June 1817 aged 37 years;

also those of his mother Margaret Jackson who died Jan 1820 aged 81 years;

also those of his widow Elizabeth Jackson who departed this life 12th

March 1880 aged 92 years; also of his only son David Jackson who died Nov 11th

1889 aged 75 years.

SOURCE: Guide to Creggan Church & Graveyard,

1988. Creggan Historical Society Journal.

|

Mattie Skuce

also recorded another grave marker from Creggan Church graveyard, but this is for a grave

that is not recorded anywhere else. It was likely

installed decades before the one that remains and hence would have been even

harder to read. Given that, I have taken the liberty of adding a few editing

suggestions in red.

|

2nd stone on right

facing church

To the memory of George Jackson

late of Creggan who departed this / life Sept 3rd 1782 aged 64

years

also to the memory of Margaret Jackson / wife of the above named.

George Jackson who departed this

life the 7th day of Dec 1797

in the 75th year of his age

and also

To the memory of their son David

Jackson late of Liscalgat. - he died

/ suddenly on the 13th day of Febry 1706

In the 8th year of his age / Also the body of Mary (Culaner +[possibly

“?”]

daughter of the above George who / departed this life 28th

September 1790 aged 70.

NOTE: Based

on other family records.

- Updated Jun 18, 2025 in the 75th year of his age - should be in the 75th year of her age.

- The death of David JACKSON recorded as 1706 at

age 8 was probably 1756. George and Margaret JACKSON had a

son, a 2nd David JACKSON (aft 1744-1796), so he had to have been

born after this first David had died.

·

Culaner was most likely Gilmer. Family

records at Gilford Castle recorded the marriage of a Mary JACKSON to a J.

GILMORE (1764-1823) some time before 1788.

·

Mary JACKSON’s age at death, based on the years

she was still young enough to give birth, means that she was more likely to

be 40, instead

of 70.

|

During my 2010

visit to Creggan Parish, a local historian suggested that this missing

grave-marker might have ended up being used as a fireplace hearth in one of the

nearby homes. After all, there were no JACKSONs still living in the parish, and

this use might have felt downright practical. In many parishes, this was not unusual. The missing slab of slate would likely have

been installed such that the lettering was not visible. Had the inscription of this lost grave marker not been found on a wee scrap of paper, an important clue to the some of the history of Creggan parish would also have disappeared.

UPDATE: June 8, 2023. North Bay Cemetery News (California): "We don't often get stones back, in this area when I was a boy, people

would take the stones home, use them for landscaping or bookends,"

cemetery volunteer and historian, Jonathan Quandt said.

3.

The following

article from the Bowen Island Undercurrent is pasted into one of my old

diaries: May 1991

It describes some disappearances of grave markers which is quite unlike the two

previous ones. In this case, it is likely that cultural bias was a factor. (My transcription - including my own emphasis - is beneath).

|

In 1966 or 1967, I and some friends visited Stanley

Park one Sunday afternoon. We came upon hundreds of gravestones piled up,

most of which were Chinese.

We asked the park attendant what was happening with

all the grave-stones and we were told that they were being used to build the

seawall.

I was young and did not think too much about this at

the time, But now, years later, I wonder exactly where these gravestones

came from and how the families of the deceased felt about their relatives’ gravestones

being used to build the sea wall.

I have photos of these stones, so I know in fact

this did occur. Do you have any explanation? - Edythe Hanen, Bowen Island.

Searching for an answer, we consulted Richard

Steele's book The Stanley Park Explorer, where at page 109, we find the

following paragraph:

“An interesting footnote to the Ceperly area is the

origin of some of the stones in the wall on the southern side of the

playground. In 1968, base slabs and name stones from Mountain View Cemetery

were trucked to this location and incorporated into the wall. All came from

so-called “junked

pieces”, discarded, damaged or replaced. The majority were

taken from the 1919 section of the graveyard. If you study the shape of the

stones used throughout. it is possible to identify which ones came from the

cemetery even though the names or other identification have been turned inwards.

A call to Margaret LaSaga at the city's Mountain

View Cemetery brought further amplification.

The stones, for the most part,

were base slabs, which are used to hold the gravestones erect. The city, faced with constant vandalism and

desecration of its only publicly owned cemetery, passed a bylaw in 1964 that

all grave markers, in future, be placed flush with the ground.

Where

permission could be obtained, upright markers were replaced with ground level

ones, and the old markers, along with the no longer needed base slabs and the

vandalized tombstones, were taken to Stanley Park to find a final resting

place.

LaSaga says extreme care was taken not to leave

any lettering showing on the face of the seawall.

Completion of the perimeter sea wall came in 1980,

63 years [after the] first section [of the seawall was built].

|

It is worth

focusing on what was left unsaid about how these Chinese grave-markers from Mountainview Cemetery came to be

used in the sea-wall at Ceperly Park. After reading this article, I had

contacted Edythe Hanen who had then mailed me her photos for a short-term loan.

Since 1991 was long before digital sharing was possible, I did a rudimentary

sketch before returning the photos.

Recently, I did a digital search - hoping to learn

more about what had happened. The 1919 Section of the graveyard can be seen in the upper left-hand

corner in the

Mountainview

Cemetery map:

This leads me to ask why - in the notes on

the 1919 section- was there no mention of the Chinese? Instead, there was just this:

1919 section.

Across 41st Avenue is a small pocket of graves which include Janet

Smith – the house maid murdered in Shaughnessy, Joe Fortes – Vancouver’s

favourite Lifeguard, and the third Firefighter’s Memorial.

Also, why were these ‘junked pieces’ discarded and damaged

in the first place? The Stanley Park

Explorer describes it as nothing more than an interesting footnote. It leads me to question the statement that: extreme care was taken not to leave any

lettering showing on the face of the sea-wall. Could there be a taint of cultural bias here? Who is

being protected?

A current Wikipedia article does mention that stone sets from the recently dismantled BC Electric Railway streetcar

system had also been incorporated into the seawall, but like the earlier article, it too mentions nothing

at all about the grave-markers taken from Chinese graves.

These days,

Canada is facing a long-overdue reckoning over the lack of respect shown by the

dominant culture to the long-lost graves of indigenous children. Ireland faces a similar reckoning as the stories of the children’s

mass grave in Tuam have begun to surface. Stories such

as these remind us of how - all too often - most cultures tend to treat the powerless, and

how this results in their place in our remembered histories getting lost. When the stories behind the disappearances of these graves come to light, we may find that we have been given at least some of the tools to right (and to rewrite) wrongs.

THE FUTURE

I can’t see myself wanting to have a grave marker to mark my passing after I die. Like so many people these days, I

belong everywhere and nowhere. Perhaps my ashes will be scattered to the earth,

to the sea or to the wind, whichever feels best to my survivors. After all,

there is not enough room for all of us living today to continue to take up more

space. Still, it does make me wonder about that sense of place and connection

that families once enjoyed when they visited graveyards. It also leads me to wonder

whether there might be another approach that could help to sustain our sense of connection to those who have gone before. Of

course, any approach that we choose can only be as durable as most things are. Ashes to ashes.

Dust to dust.